Interviews & Published Work

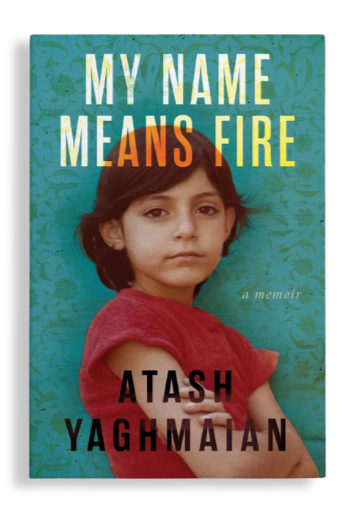

When it came time to write my memoir, My Name Means Fire, I chose to write it in English. “In English, I’m just someone—free, unclaimed, and therefore, for the first time, self-defined.”

Had I written about my life in Persian, I would have softened the edges. I might have told the story of a girl who left Iran, but I would never have talked about…

Click here for a neudivergent-friendly version of the full essay

Conversations with first-generation immigrant women building new lives from scratch. Every episode explores real decisions, tensions, and transformations behind leaving home, starting over, and figuring out who they are in places that don’t always see them clearly.

Iranian-American therapist, writer, and activist Atash Yaghmaian joins Arrivals to discuss her debut memoir, My Name Means. We discuss stigma, how writing helped recover memories, leaving Iran at nineteen, and building a life in New York.

I met Atash Yaghmaian the way I meet all my friends these days, on the dance floor. Over coffee in the East Village, Atash and I got to talking about her childhood in Iran during the revolution and the trauma inflicted on her from an early age by strangers and family alike…Several months into our friendship, she leaned in and whispered to me, “I am multiple.”

“Meaning what?” I asked.

In an interview with Terry Hong for Shelf Awanress, we answer the often-asked question: "But how did you survive?" plus many more. To endure a childhood defined by horrific experiences, we "left reality. Just like that."

"Many people with our condition end up killing themselves.... We wrote this book for them, and for all who are ready to heal their childhood traumas."

The young men and women protesting in Iran today are not just fighting an Islamic regime. They are fighting their fathers’ and brothers’ passive agreement with the idea that female sexuality must be controlled.

The current protests in Iran have filled immigrants like me with so many different emotions. But whatever happens, one of the most beautiful outcomes of this moment is that, for the first time, many Americans are seeing Iranians as separate from their government.

In the summer of 1988, while still in high school, I got involved with an underground feminist group in Tehran as a courier, secretly transporting backpacks full of pamphlets to other activists, who then distributed them at night to women’s clinics where nurses handed them out to patients.

People-pleasing is a method used by children to create safety. It’s a defense mechanism that creates a bit of order in the midst of chaos. People-pleasing will continue in adulthood as long as our childhood traumas remain untreated.

I lived in a tent for a month. Not a refugee tent, though I am an immigrant from a war-torn country. But no, this was a dark-blue camping tent pitched in the middle of the living room, because I didn’t want to have anything to do with my boyfriend. And yet, I couldn’t leave him. I didn’t have a voice back then. So I gave myself a tent.

Some people are born knowing what they want to do for a living. For others, it takes a lifetime of hustle and trial-and-error to figure that out. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter how long it takes to find your vocation, or where you start. Sometimes, the most unlikely of jobs can put you on the path towards a fulfilling career. Since I was a little girl in Iran, I’ve always loved stories.

I killed someone. Or so I thought.

When I was a little girl in Tehran, during the Iran-Iraq War, the radios would often speak lovingly of the dead. “Such an honor to have been chosen by God,” they’d say of the martyrs who died fighting. I wondered where this place of honor was or how people reached it, but I never thought to be sad. Death was a privilege I was still too young to know.

Have you ever thought about changing or improving your life by moving to a new location?

It’s called “pulling a geographic” and I first heard of the term in a twelve-step program. It immediately got my attention. “Pulling a geographic” means changing one’s physical environment in the hopes that one’s problems will magically go away in the new place.

I hadn’t thought about my brother much since I’d left Iran. I assumed he’d found his own way. But one day, when I was on the phone with my folks back home, I asked to speak with him.

“Your brother isn’t talking,” my father said.

“To me?”

“To anyone,” he said. “He refuses to see a neurologist or even a family doctor. It’s been like this ever since he was released.”

When I came to America, I learned a lot about the importance of being an individual. I loved that idea. It wasn’t something I was exposed to much in Iran. My own childhood experience was defined by being told that I had to sacrifice everything for my family and community. I learned to feel that I was nobody; as though, on my own, I didn’t exist…

As a therapist, I get this question a lot. “How do you know what is the right relationship for you?” I sense that my clients are looking for an easy checklist, but the answer I give is a bit tougher. The good news is that the answer to this question often already lies within you - your past and old patterns that persist.

I connected to the power of affirmations back in graduate school. I had heard about mantras and knew that words have power, but I never really thought affirmations would have a concrete effect on my mental health, until I started actually working with them.

I’m going to share with you what I have learned in my life and clinical practice about how to use positive affirmations to create new visions of what is possible…

Trauma is widespread, and most people experience some form of trauma during the course of their lives. I myself am a survivor of complex trauma and can attest to its tenacity and destructiveness. I’m also a therapist who has seen, time and again, that healing trauma really is possible: through talking, writing, transparency, and sharing stories. This is why I am dedicated to sharing some of the things I have learned, both personally and professionally.

Ever since I was young, I’ve lost track of time. When I was a child and lived in Iran, whole days and weeks would disappear, along with all the bad things that happened to me during that time. When I was older and studied psychology in America, I learned about dissociation and its roots in trauma.

I was an undocumented immigrant living in New Jersey in the first a few years of my arrival to America. I had moved from New York to the Jersey Shore in hopes of studying at Atlantic Community College, the only college that accepted me without papers…

I had very little freedom as a teen in Iran. My stepfather kept a close eye on me. He used to drop me off and pick me up from school to make sure I wasn’t doing anything to “damage our family’s reputation,” so the only time I could be alone was when I cut classes and hung out down by the beach.

We had moved away from the busy city of Tehran to a deserted town on the Caspian Sea, because my mother suffered from severe social anxiety and couldn’t deal with any noise. As a kid, I used to love being there and looked forward to summer vacations, but as a teen, life there felt small, isolated and lonely…

“How to ruin a Persian wedding” - Ruminate Magazine (2020 VanderMey Non-fiction Prize)

The summer I was seventeen, my mother’s preoccupation with marrying me off to a rich suitor reached a fever pitch. I wanted to get out of her house too, believe me, but I fantasized about being like those independent heroines in Western novels who are optimistic but alone. “Tomorrow is another day,” I would tell my mother, after sifting through all of Scarlett O’Hara’s lines from the Persian translation of Gone With the Wind we kept around the house. “Akh akh,” my mother would say. “Disgusting. You want all those dead husbands and divorces, don’t you?” But she backed off — for a while, at least…

Marco was waiting for me outside Jivamukti Yoga Studios, leaning against a white Ferrari. He held the door for me and I got in.

“Okay, yoga girl,” he said. “What do you feel like eating?”

“I don’t care,” I said. “Let’s just drive.”

This was our first date. Spring 1998. We drove to the South Street Seaport. We walked around talking about our moms and watched the bridges that span two boroughs…

I was so happy to find out it was normal to have imaginary friends. I learned this information in my college child development class one day, when my professor spoke to us at length about the “boy” who kept him company when he was young. My professor was a lonely, only child, but he had an invisible friend with whom he would eat meals and share his toys. “After a few years,” my professor said, “I outgrew the whole thing.”

“Did he just admit to having an imaginary friend?” I asked the girl next to me. She giggled and nodded…

In 1978, I was a seven-year-old girl living in Tehran. My memories from that time are child-like and simple, yet I often find that what I experienced then has shed more light on my understanding of today’s Iran than any current political analysis could do. As I watch the protests against the Ahmadinejad regime unfold from my new home in Brooklyn halfway across the world, I am struck by how similar the spirit of the current protests are to the uprisings that occurred almost exactly thirty years ago. People often ask me if I think the supporters of Mousavi will undo what the Iranian Revolution accomplished in the late seventies – as if these two movements were fundamentally different. I tell them, optimistically, that what we are witnessing today is simply the continuation – and hopefully fulfillment – of what my parents started when I was a child…